Fossils are informative about the evolutionary history of species on earth. However, they are lacunary. Molecular phylogenies, reconstructed by comparing genetic sequences of modern species, provide another and complementary source of information, which, once combined with fossils, allows for a deeper understanding of the processes shaping biodiversity over time.

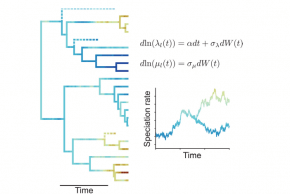

In this study, Quintero et al introduce a new model of species diversification at the macroevolutionary scale, combining information about phylogenies and fossils and accounting for fine-grained variation in the rate at which different lineages diversify. They propose efficient computational methods for fitting this model to empirical data. When applied to placental mammals, their model contradicts the classical view of an increased rate of diversification of placental mammals triggered by the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction (which occurred 65 million years ago and was responsible for the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs). Instead, the global rise of placental mammals would have been the result of a preferential extinction of slowly speciating lineages. Thus, diversity seems to have been brought about by multiple and isolated fast-speciating lineages, rather than by a single or a few punctuated innovations.

For more information, refer to the original article.